With virtually no R&D department, no blockbusters, and stifling

generic pressures Big Pharma is not in a happy place today. Many multinationals

have gone the licensing and acquisition way, but increased crowding on the shop

floor is resulting in largely over-priced deals. Vaccines are a seemingly hot

area of acquisition, whilst oncology has seemed to be all the rage for the past three years. Amgen paid a whopping US$ 1 billion to the vaccine

specialist BioVex for its OncoVex cancer vaccine in 2011, Biogen acquired

Stromedix for US$ 562 million and Gilead acquired Calistoga for US$ 600

million—all relatively over-priced deals, even for unmet niche targets.

In fact, the average takeover premiums for biotech companies are nearly

double the premiums of acquisitions in other industries in the current markets.

The game of panicky music chairs occurring in the industry is generally

indicative of the multinationals’ desperate efforts to explore cost-cutting

alternatives in the R&D department, as well as to access new areas of growth.

Big Pharma Eager to Acquire

The number of licensing

agreements has also increased by a substantial 16% in the last five years.

Notably, in anticipation of the patent cliff, the majority of licensing deals

struck in Q2 of 2010 involved molecules in marketing stages of development;

leads in phase III trials were the second most popular licensing target.

In-licensing cost Big Pharma US$ 25 billion in 2010, and sales from licensed

products amounted to ~26% of total sales. In the US, venture-backed Life

Science M&A exits massively soared last year, and exit volume reached unprecedented

levels, even in comparison with biotech’s 2007 peak (Fig 1).

Figure 1. Exit volume & number for US Biotech, 2005-2011

Source: Silicon Valley Bank, 2012

Figure 1. Exit volume & number for US Biotech, 2005-2011

Source: Silicon Valley Bank, 2012

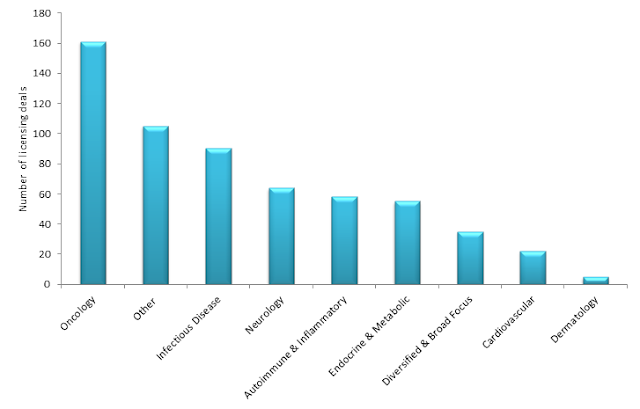

In-licensing activity stats show

that oncology and neurology currently dominate the target disease field (by licensing activity - Fig. 2). Interestingly, in line with vigorous pharmerging expansion, infectious disease has made a comeback hit last year. All of this is in stark contrast with the biggest blockbusters of the last decade, who have for the most part

targeted pervasive “first world” conditions such as stroke, heartburn and

asthma. Because like the likes of Lipitor have now gone generic, cardiovascular health has dropped to the bottom of the popularity rankings.

Figure 2. Licensing

activity volume by therapeutic area, 2011

Source: Deloitte Licensing Deals, 2012

The Biotech Declaration of Independence

With shrinking pipelines, Big Pharma are left with little

choice but to streamline efforts towards partnerships and licenses.

Bristol-Myers’ “String of Pearls”, and Lilly and Merck’s novel

aqcuisition-focused business models, discussed in our previous post, serve as

testimony to that. However, the visible whithering of the pharma giants’ power

is also strong incentive for smaller players to challenge industry leaders and

to dodge “Pharmocracy’s” sphere of influence.

Enough lone biotech examples have

now emerged to conclude that the No-Exit trend is now a dawning reality, rather

than mere speculation. Beside the fact that US equity valuations already prefer Biotech to Big Pharma, there is now an

impressive collection of biotechs valued between US$ 500 million and US$ 3

billion who have chosen the independent route, with impressive results.

Why Big Pharma Has Lost its Appeal

Intuitively speaking, the traditional exit model

postulates that a biotech’s value is commonly created, and indeed dictated, by “the

exit”—a highly coveted event for a small player. But in the current industry

scenario this may no longer be so. For starters, Big Pharma are now nowhere

near as intimidating in terms of scientific capital and IP as say, ten years

ago—which means that biotechs now have a realistic chance at competition with

conglomerates. Secondly, investor confidence in the lone biotech is growing as

markets are beginning to fathom the actual benefit ratio of a modern Big Exit.

All factors considered, today, a small player transfers

substantially more value to Big Pharma in a licensing deal than it receives in

return. After all, both are now likely to use the same tools in reaching the

market—Contract Research, Manufacturing, Sales and Marketing organizations. Even

the famous marketing departments—the force Big Pharma could proudly boast to exit

anticipators—are on a visible decline. In turn, the CRO (contract research) and

the CSO (contract sales) industries have grown at lightning speeds since the

onset of the Patent Cliff, as they have received the shifting volumes of Big

Pharma’s R&D projects and became a viable, affordable option for small

biotechs. Almost all of the future growth CROs are poised for is expected to be

driven by biotechs, rather than by pharma multinationals.

Access to Global Markets

Luckily for Big Pharma, the CSO market at the moment is

still heavily concentrated in developed economies. In China, only a small

number of CSOs are currently in operation; leaders include NovaMed, with 500

representatives, and Invida with roughly 600. In India the number of CSO

players is lesser still. For the most part, this is due to lack of

appropriately skilled personnel on the ground, but global talent migration is

likely to compensate for low volumes in the not-too-distant future.

It is because of their pharmerging market presence that pharmaceutical giants remain confident that their lingering, unbeatable allure rests with their global coverage. DIY biotech strategies may pay off in local markets, but the chances of unpartnered companies reaching global markets are still rather slim. Needless to speculate, burgeoning service provider industries are just as eager as Big Pharma to reach foreign shores, and the lone player may be granted global market access sooner than multionationals would like to believe.

It is because of their pharmerging market presence that pharmaceutical giants remain confident that their lingering, unbeatable allure rests with their global coverage. DIY biotech strategies may pay off in local markets, but the chances of unpartnered companies reaching global markets are still rather slim. Needless to speculate, burgeoning service provider industries are just as eager as Big Pharma to reach foreign shores, and the lone player may be granted global market access sooner than multionationals would like to believe.

Raising Capital the DIY Way

In terms of financing, Big Pharma are now in much lesser

possession of cash flows than before they went on a cliff-induced panic

shopping spree. Furthermore, pharma executives are naturally shopping around

the therapeutic areas which are highly lucrative on their own, namely areas of

unmet need and with well-defined patient populations which would warrant a

lesser marketing force. In the charts of investors’ priority lists, clinical

trial success and FDA approval are fast becoming top hits, pushing out the

traditional value-creating partnership. As investors are beginning to

understand that clinically and comercially sound lone players have the

potential to generate more value than partnered ones, the markets are beginning

to reward the DIY system, generating more cash for biotechs who would otherwise have no choice

but to resort to the exit.

Crowdfunding

Governments

are likely to play a role in Biotech survival too. France has had a

crowdfunding scheme, titled “Fonds Communs de Placements dans l'Innovation”—roughly meaning

the Communal Innovation Fund—for over 15 years, raising around US$ 6 million from

the crowd for the greater scientific good. The British Bioindustry Association has

recently picked up and improved on the idea, initiating the “Citizens’ Innovation Fund”

which promises lucrative tax breaks and reasonable returns for those supporting

the bio-industry with investments of over £15,000 a year. Crowdfunding is probably a rather infantile notion as of yet - but with schemes such as the CIF this way of raising capital likely to play an increasingly crucial role in safety-netting the lone biotech arena.

It seems the giants may be under a realistic over-shadowing threat from audacious young biotechs eager to go it alone. Perhaps it is too early to tell who will win out in the long term, but Big Pharma could certainly do with a disruptive business strategy in order to regain its appeal in the eyes of the biotech--and the world. Change is undeniably in the air, but only time will tell whether Big Pharma will be able to gracefully regain composure, or whether the industry will once again return to its very foundations of lone players and great innovations.

It seems the giants may be under a realistic over-shadowing threat from audacious young biotechs eager to go it alone. Perhaps it is too early to tell who will win out in the long term, but Big Pharma could certainly do with a disruptive business strategy in order to regain its appeal in the eyes of the biotech--and the world. Change is undeniably in the air, but only time will tell whether Big Pharma will be able to gracefully regain composure, or whether the industry will once again return to its very foundations of lone players and great innovations.

No comments:

Post a Comment